Now Reading: Face to Face With the Scale of the Cosmos

-

01

Face to Face With the Scale of the Cosmos

Face to Face With the Scale of the Cosmos

As dusk fades to night in the Atacama Desert near San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, an observer contemplates the planets, stars, and galaxies dotting the darkening sky.

For most of us, to see a truly starry night isn’t easy. I have been writing about dark skies and light pollution for almost 20 years. And I have seen some breathtaking skies—southern Morocco at the edge of the desert so plush with stars it still seems like a dream, the Racetrack in Death Valley with stars rising in the east and dropping off the edge of the world in the west. At other times when I’ve gone to see the sky, I found too much humidity in the air, or too many clouds, or the obscuring smoke from a burning world. In the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa, the famous skies were veiled by a freak sandstorm from the Sahara.

But the main reason that city dwellers can no longer see a starry night is simply all the artificial light we waste into the sky. There’s even a scale for this—the Bortle scale, named after an amateur astronomer in New York state who grew tired of younger astronomers inviting him out to supposedly dark viewing sites only to find those sites not so dark. John E. Bortle’s scale goes from 1 to 9, from darkest (no artificial light on the ground or in the sky) to brightest (inner cities).

Most people will live the majority of their lives in level 5 or above, without the experience of a naturally dark sky. And ever-increasing numbers of people live in areas with levels of 7, 8, and 9. They may think of these bright levels as normal, what “darkness” is supposed to be.

Over the past decade, the shift from electric light to electronic lighting—in the form of light-emitting diodes—has made the problem worse. LEDs are generally brighter than traditional electric lights, often emit more blue-white light, and are more energy efficient. But too often this efficiency means we use more of them, creating more artificial light at night. A recent study estimated the growth of light pollution worldwide from 2011 to 2022 at 10 percent per year, a doubling roughly every eight years.

RELATED: Lighting Up Yosemite

Despite these conditions, Bortle Scale 1 areas still exist, just not where most of us live. When I asked a friend at the U.S. National Park Service—whose Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division measures levels of darkness throughout the National Park System—where to find a dark sky, he hesitated to name anywhere in the lower 48 states. The Outback in Australia would be a good place, he said, or Chile.

And so I’m here, traveling with Pedro Sanhueza, an environmentalist and longtime dark-skies advocate who has devoted the past two decades to protecting his country’s dark skies. As we drive, Pedro tells me that in the 25 years he’s lived in La Serena, the population has almost doubled, and the lights have grown, too. The sleepy city where the Milky Way used to spend the night in everyone’s backyard is getting so big that astronomers in the Elqui Valley are beginning to worry, even as billions of dollars go into building new observatories like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory at Cerro Pachón.

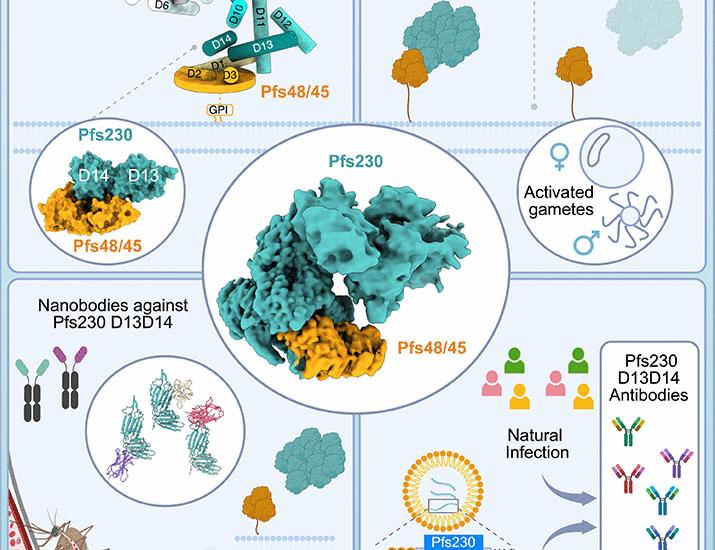

This image illustrates the 9-point Bortle scale, which quantifies the impact of light pollution on the darkness of a night sky at a particular location. Star visibility increases dramatically from left (urban areas with heavy light pollution) to right (excellent dark-sky conditions).P. Horálek and M. Wallner/ESO

This image illustrates the 9-point Bortle scale, which quantifies the impact of light pollution on the darkness of a night sky at a particular location. Star visibility increases dramatically from left (urban areas with heavy light pollution) to right (excellent dark-sky conditions).P. Horálek and M. Wallner/ESO

Still, tonight seems promising. The sky is mostly clear, with no storms in the forecast. Northern Chile boasts more than 300 nights of clear skies a year, and I’m grateful to see only two clouds overhead. As we leave the main highway and begin to wind through the mountains, I’m hopeful we’ll find the kind of darkness that so many places have lost.

For 20 minutes, we creep around curves and navigate road repairs, ours the only car. Bats flicker above the gravel, a statuelike owl perches on a bare roadside limb. The mountains disappear as we climb, as does the road behind us, and we see only the world our headlights carve from the dark. Part of me wishes we could turn the headlights off too and ride beneath a sky filling with stars. But the rest of me knows this is a terrible idea.

When we finally arrive at our destination, a small private observatory with two large telescopes, I am stunned by the brightness of the sky. In a line stretched back toward La Serena, three planets—Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter—glow like passenger jets in low approach for landing. Though I’ve never seen it before, I recognize the Southern Cross immediately, its shape shining just above a mountain’s ridge to the south. The constellation Orion catches my eye, its iconic three-star belt so familiar—until I realize it’s upside down from how I see it back home. Nearby glows the red eye of Taurus the Bull, the star of Aldebaran, only 65 light-years away. If you kept to highway speeds, it would take 800 million years to get there by car.

When you get to a place that is still naturally dark and see a night sky like the one our ancestors knew, what you feel is recognition…reconnecting with something you maybe didn’t even know you’d become disconnected from.

Someone points out the Magellanic Clouds, galaxies visible only from the Southern Hemisphere. They’re clouds of stars. “Yes, tens of thousands of millions,” says Pedro. The Large Magellanic Cloud alone is estimated to have 30 billion stars. And distances? The Large Magellanic Cloud lies about 160,000 light-years from Earth, the Small Magellanic Cloud about 200,000 light-years away. We use light-years—the distance that light can travel in a year—to talk about distance in space. In this case, that’s 160,000 or 200,000 multiplied by 9.5 trillion kilometers. And these are among the closest galaxies to our own Milky Way. At this, my brain begins to spin—how are we to grasp such numbers? “Even astronomers can’t truly grasp these scales,” the popular astronomer Phil Plait writes. “We work with them, and we can do math and physics with them, but our ape brains still struggle to comprehend even the distance to the moon—and the universe is two million trillion times bigger than that.”

When I hear such numbers, I can’t do much but nod. And that’s okay. To stare into the sky unable to grasp what you see, the numbers and distances bending your brain beyond its reach, is part of what makes this experience so valuable—a reminder that we are not in control of everything, our anxieties are small, our lives brief, and all the more reason to savor what we see, now and here. Rather than feeling overwhelmed, seeing these distant objects causes me to feel connected to something incomprehensibly larger than me. And from this a wonder at being alive, and the welcome thought that I get to exist in a universe where this exists, too.

As we stand watching, I tell Pedro I’ve been thinking about the idea of “scale,” how we make sense of the distances and numbers in the night sky, and even the question of what good it does to look further and further into space.

The lights of the town of Andacollo, Chile, were visibly reduced [top] during the Blackout for Our Skies event, as seen from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. After the event [above], the level of light pollution returned to near-normal levels.Photos: D. Munizaga/CTIO/NSF/AURA/NOIRLab

The lights of the town of Andacollo, Chile, were visibly reduced [top] during the Blackout for Our Skies event, as seen from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. After the event [above], the level of light pollution returned to near-normal levels.Photos: D. Munizaga/CTIO/NSF/AURA/NOIRLab

Earlier that day, I’d mentioned the idea of scale to Manuel Paredes, my guide at the Cerro Tololo observatory. “On the hierarchy—or scale—of needs, you have to have food and water and shelter, but life isn’t only those basic needs,” he said. “There’s also a more philosophical or spiritual or soulful desire to look out there. And with looking to the night sky, trying to understand specific things like, What is a star? What’s the sun? What is a supernova? Through these small questions, we are trying to answer these big questions, trying to get some satisfaction. I think that there’s a need to understand our position in the universe very deep in our brains and in our hearts.”

When you get to a place that is still naturally dark and see a night sky like the one our ancestors knew, what you feel is recognition. It’s the feeling of reconnecting with something you maybe didn’t even know you’d become disconnected from. It’s the way the voice of an old lover or friend rings through your body when you hear it again after some years. It’s related to the way that images of the night sky—as stunning as they may be—aren’t the same experience as seeing the sky for yourself.

This deep connection makes me recoil from the next thing I see: a long train of satellites rising from the horizon toward orbit. Before this, we had watched the slow scrawl of individual satellites, slight incisions on the black fabric overhead. I admit that I still feel some thrill at the sight, a thrill left over from my first sight of satellites near a northern lake decades ago. But when I was a child, there were only a few hundred of these artificial lights in the sky, and their uniqueness added to the wonder of the stars. Since then, the scale of their growth has been overwhelming. The number has already swelled to around 12,000, and predictions are for 100,000 or more in a decade. Astronomers and dark-sky advocates have been sounding the alarm, warning that our night skies, especially after dusk and before dawn, when most people look to the sky, will become crowded with as many “moving stars” as static stars.

We are cutting ourselves off from so much that might inspire us, from scales of time and distance and numbers that offer a chance to feel awe and wonder at this world where we live.

Pedro doesn’t hold back about the satellites. “I hate them so much,” he says. “This is industry without control.”

Much of his present work centers on helping Chile’s mines comply with national laws limiting artificial light, a vital task in a country where mining produces more than half of the exports, including nearly a quarter of the world’s copper and 30 percent of its lithium. At night, the mines shine like small cities, Pedro explains, but he’s been able to make progress, a result he attributes to the large number of engineers the mines employ. “The mines have many well-prepared people,” he says, “and so if you explain in the proper way the technological solution, they will make the change.”

He and the rest of the astronomical community currently face an immense challenge from a proposed new mine in the Atacama Desert, uncomfortably close to some of the most important observatories. Pedro calls the INNA project—a proposed 7,400-acre (3,000-hectare) green-hydrogen production facility—“very bad for Chile,” with the light pollution, airborne dust, and atmospheric disturbance “underestimated systematically, the projections very limited and superficial.” Nonetheless, he says, the mine may be approved by a national government hesitant to turn down the tax revenue the mine owners insist it will bring. This seems to be the perpetual dilemma when it comes to light pollution: the promise of economic gain for some at the expense of a dark-sky heritage that belongs to everyone.

I think about my 6-year-old daughter, and the future sky any child anywhere will know. The inexorable spread of artificial light, the explosion in the number of satellites—on nearly any scale of time, these changes have happened in an instant. Beneath the Chilean night sky, the suddenness seems even more startling given the scale of astronomical time, where the faintest light we can see left its source about 13 billion years ago. The erasure of this experience robs us all, and especially future generations who will never see a night like this. That the costs of such loss are intangible makes them not a bit less important. We are cutting ourselves off from so much that might inspire us, from scales of time and distance and numbers that offer a chance to feel awe and wonder at this world where we live.

Even here, the lights from La Serena are rising on the western horizon to erase what low stars we might have seen. “We are losing 30 degrees above the horizon,” Pedro says. “We are fighting almost every day a new offender.” Here in Chile, a long strip of country where astronomers come to find the driest, clearest darkness in the world, the risk is that such darkness—and all the celestial beauty it brings—will slip away. There’s no reason it has to, and for now there is still time.

But if we do nothing or not enough, we will lose nights like these here as we have lost them in so many other places. And the evening drive from La Serena will bring us only to somewhere darker than the city we left, rather than back in time to a world every human once knew.