Now Reading: Denisovan Fossils Reveal Enigmatic Hominins’ Vast Range from Siberia to the Tropics

-

01

Denisovan Fossils Reveal Enigmatic Hominins’ Vast Range from Siberia to the Tropics

Denisovan Fossils Reveal Enigmatic Hominins’ Vast Range from Siberia to the Tropics

Rapid Summary

- A fossilized jawbone found off Taiwan’s coast has been confirmed to belong to a male Denisovan, marking the third verified location of Denisovan remains.

- Denisovans were archaic humans who adapted to diverse environments spanning siberian snowfields, Tibetan high altitudes, and subtropical jungles in East Asia.

- DNA evidence shows Denisovans thrived across East Asia for hundreds of thousands of years but left behind scarce physical remnants; their discovery was first made in 2010 through a Siberian finger bone.

- The newly identified jawbone (Penghu 1), dredged from Taiwan’s Penghu Channel before 2008, was analyzed using protein markers after its DNA was deemed too degraded for identification.

- Comparisons confirm that Penghu 1 resembles another robust Tibetan mandible linked to the Denisovan lineage. Protein analysis verified it conclusively as belonging to this group.

- Despite limited direct fossils, instances of interbreeding between early modern humans and genetically distinct populations of Denisovans have been recorded through genetic markers found in present-day humans across regions including Oceania and Southeast Asia.

Image Captions:

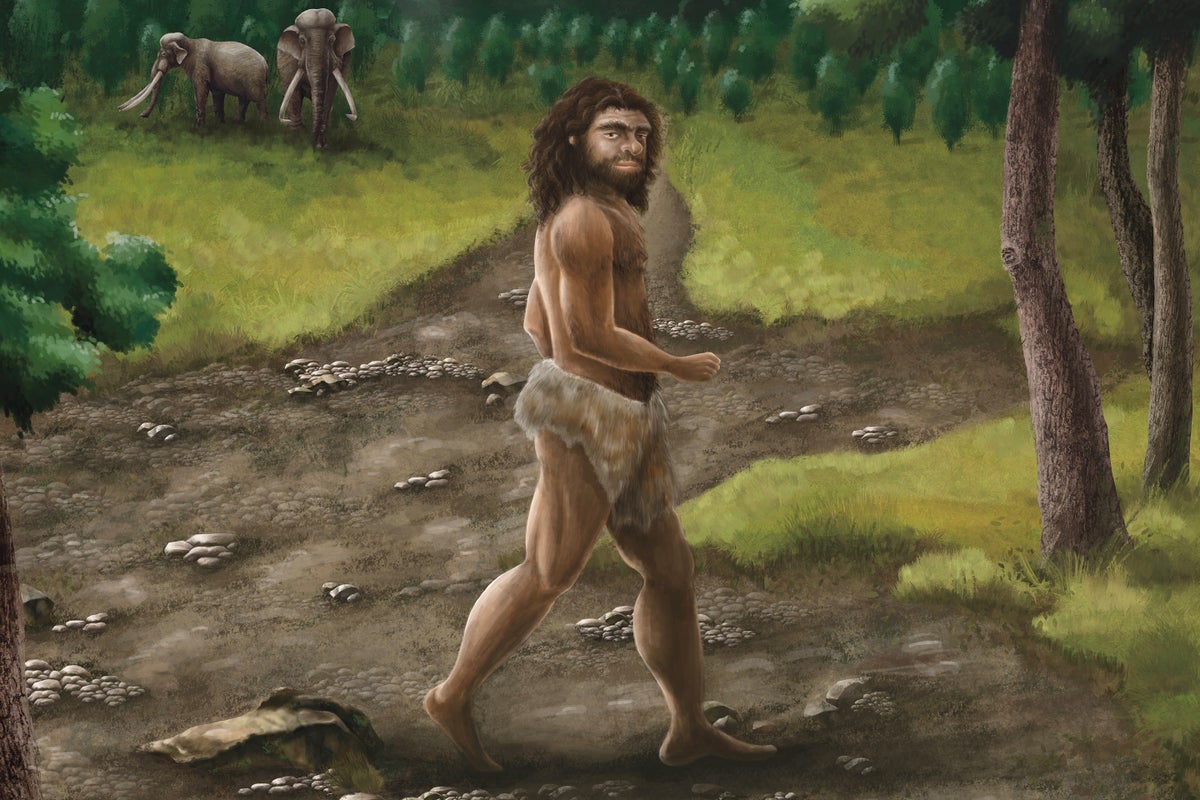

- Illustration depicting a robust Denisovan male walking near Taiwan (by Cheng-Han Sun).

- Photo showing Penghu 1 jawbone viewed from right side and top (by Yousuke Kaifu).

Indian Opinion Analysis

The discovery highlights the extraordinary adaptability of archaic human groups like the Denisovans,who thrived across vastly different climates over thousands of years-a factor that resonates wiht India’s own ancient contributions on evolutionary timelines. While their genetic traces are less prominent in South Asia than Oceania or Southeast Asia, further potential genomic research could uncover connections relevant to india’s prehistoric populations or migratory paths.

This finding enriches global understanding of early hominin migrations and emphasizes advancements in protein-based fossil analysis as an alternative when DNA preservation is poor-significant for tropical regions like India where climatic conditions challenge traditional genetic studies. Scientists’ ability to piece together fragmentary evidence aligns with broader efforts worldwide targeting gaps in human evolution narratives.